|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

|

THE ABORTED VOYAGENo Gilligan's Island and no warm welcome-back for real deckhandsby John MerriamEditor's note: names have been changed in this article to protect identities. I was his second lawyer. After firing his first one, and consulting with at least two more, Steve showed up in my office. He said he had a bad back and nightmares of drowning after trying to deliver a yacht to Honolulu from Seattle's Fishermen's Terminal. Steve needed a lawyer to force the boat owner to pay him injury benefits under the federal maritime law because he was hurt at sea, beyond the reach of state-based systems of workers' compensation. Steve was 35 years old and a long-time resident of Seattle. He was a remodeling worker by trade although, as I would find out later, he wasn't licensed and bonded by the state of Washington. He made between $25,000 and $50,000 per year, depending on the work. In November 2003 he was hired to help remodel a fancy condominium in an expensive neighborhood of Seattle. The owner of the condominium, Grant, promised Steve $750 for the job, but paid him only $500. But by the time he realized he was getting stiffed for $250, Steve had much bigger things to worry about. Working with Steve was a guy named Mitch who was in charge of the remodel. Grant earlier sent Mitch to pick up a motor yacht he had purchased, a 75-foot sportfishing vessel of 100 tons. Mitch motored the boat across the Atlantic Ocean, through the Panama Canal, and to Seattle. According to Steve, Grant asked Mitch to deliver the yacht to Honolulu after he finished up at the condominium. Mitch needed two deckhands to help him make the delivery. Steve later told me that Grant got a good deal purchasing the yacht because it was in need of maintenance. Mitch and Steve finished up Grant's remodeling job. Mitch offered Steve the yacht-delivery deckhand job and asked if Steve knew of someone to serve as the second deckhand. The terms for the deckhands were $1,000 each and a plane ticket from Honolulu back to Seattle. The deckhands only had to do the cooking and stand a daily four-hour wheelwatch, each, while Mitch slept. The deckhands could fish for marlin and tuna on the way. It sounded like a paid vacation! Steve quit his regular job and called his friend, Tim, two days before the yacht was scheduled to cast off. "Hey, Tim, I've lined up a dream job delivering a yacht to Hawaii and she needs an extra hand." Steve described the job offer. Steve met Tim in the late 1980s when they both worked aboard a factory-trawler in Alaska. Tim got hurt pretty bad and had quit commercial fishing. He had since gone to law school and had just passed the bar examination, but he didn't have a job and was at loose ends. "I'm bringing my golf clubs and you could, too," Steve continued. "We wouldn't have to come back right away. I've got a call in to a friend over there to see about lining up some remodeling work. The owner said we could live on the yacht for a while if we stay in Honolulu." Tim accepted immediately. The yacht departed from Fishermen's Terminal on November 23, 2003, crewed by Mitch, Steve and Tim.

Steve sat in my office and related the following tale: "The trouble started four days later, 300 miles off the coast of Crescent City--near the border of California and Oregon--in the wee hours of Thanksgiving Day. I was at the helm while Mitch and Tim slept. At 0230 or 0300, the seas were 15-20 feet, with the wind picking up, and I guessed we were running into a storm. The port engine started running rough and then died. Then the starboard engine quit. Shortly after that the generator stopped running. I ran to wake up Mitch and Tim. The weather got worse and it started to feel like a real storm. After the generator quit the emergency battery system kicked in, but the batteries went dead after a few minutes and the lights went out. It was completely dark. I tried to radio an SOS, but without power the radio was dead too. The weather kept picking up. My stomach had a vacant feeling, like it was empty and I was all alone. "Mitch and I got a flashlight and saw that the fuel lines were totally clogged with what looked like fudge. Some sort of fungus had been growing in the fuel tanks. I asked Mitch if the fuel tanks had been cleaned before we left Seattle. He said they hadn't, nor had the emergency batteries been replaced. Mitch said Grant was waiting for Hawaii before doing maintenance. That pissed me off. I used the anger to get me through what came next. "The afterdeck of the yacht held extra diesel fuel in plastic bladders to get us to Hawaii. I ran a garden hose from one of the fuel bladders directly to the generator. After a few hours we were both completely soaked with diesel but we got the lights back on. That made it easier to get clean fuel to one of the engines. Mitch and I ran another section of garden hose directly to the fuel filter for the port engine, as the storm tossed us about. We finally got one engine running. "The engine space was only three-and-a-half feet high." "How tall are you?" I interrupted. "6 feet 2," he responded. "I was down there for a long time, hunched over. I had to run the hose back and forth between the port and starboard engines. There was no time to think about being scared. Every time the fuel filter got clogged on one engine, I would switch to the other, then clean the clogged filter. I had to repeat that process every 30-60 minutes. My back was cramping but there was an emergency to deal with. Diesel was everywhere. Once, while going down the steps to the engine room, my feet shot out and I landed on my back. That really hurt, but I kept working. There was no time to think about being injured, either." "Where were Mitch and Tim during this time," I asked "Tim told me he was really scared, and pretty sure he was going to drown. His dream job turned into a nightmare. Tim has a steel rod in his neck. He couldn't bend over to go in that cramped engine space. He stayed at the wheel, trying to keep our bow into the storm. That was a hard job. Before we got the port engine running, it was impossible. Mitch helped me with the fuel lines and filters. After we got propulsion, I told him my back was fried and I couldn't stay in the engine room anymore. Mitch said he would take care of the situation, switching back and forth between fuel filters on the port and starboard engines. But he gradually started to lose it from the stress and fatigue and I had to keep checking on him. As the hours and days passed, he got no sleep and became more and more irrational. "We spent most of Thanksgiving without propulsion. We got out the survival suits and were ready to put them on at a moment's notice. The storm finally started slacking off but I was still afraid one of the waves would come over the stern. We had the hatch to the engine space open so we could run the garden hose directly to the engines from the fuel bladders. A couple of good-sized waves would have filled the engine space and probably sent us to the bottom. Even after we got underway with one engine, we were going so slow that a following sea could have overtaken us. "And talking about a following sea, I didn't notice there was no hydrostatic release for the life raft on top of the wheelhouse. Tim thought we would have been better off if we'd abandoned the yacht and gotten into the life raft. He told me later that the raft was lashed in place with nylon line. That meant that if we capsized, the raft would not surface because it wouldn't break free. Even though the yacht is a 75-footer, I've heard of bigger boats capsizing after they broached in a following sea. "Limping along at three or four knots, it took us three or four days to get back to Cape Flattery and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. We contacted the Coast Guard after the radio was working. They kept in contact with a call every hour, and boarded us for a safety inspection in Neah Bay after we anchored to spend the night. "We spent the next night tied to a dock in Port Angeles. Tim and I went to a tavern and got drunk. "Our so-called voyage ended where it started, at Fishermen's Terminal. I think that was December 3rd. Grant refused to pay us at first, saying we hadn't completed the delivery. Tim got another lawyer, my first one, to write a letter demanding our wages. Grant paid us $1,000 each but there's been bad blood ever since. When Tim and I went back to the yacht to get our gear, Mitch had it stacked on the dock. He said Grant told him to call the cops if we set foot on the boat. And to pour salt on my wounds, Mitch told me that Grant said he wasn't paying the last $250 for the job at his condo because I hadn't earned it. "That's the last contact I had with the boat, Grant or Mitch." "Did the yacht ever make it to Hawaii," I asked. "I think it's still here, at Fishermen's Terminal." "What do you want me to do?" "I want a doctor to look at my back. My first lawyer totally screwed up the case!" "I'll see what I can do." I handed Steve a fee agreement.

Steve's case was complicated by the fact that he was a stoic and didn't seek medical treatment for almost two months after he hurt his back. Even though he had a serious injury, Steve hoped he would be cured by Father Time. The problem was compounded when his first lawyer demanded only wages from Grant, making no mention of injury for more than two months. That allowed the insurance company lawyer to argue that Steve hurt his back before or after he was on the yacht. In a lawsuit filed in federal court in Seattle, I made three written motions to get Steve authorization to see a doctor. All were denied. Judge Zilly ruled that the facts were in dispute, and that a decision needed to await trial--scheduled for September 2005. More than a year after Steve hurt his back, I worked out a compromise with the insurance company lawyer, whereby Steve could receive limited medical attention. I also amended the lawsuit to claim the $250 Steve had been stiffed on the remodeling job. It turned out that contractors like Steve are not allowed to sue anybody unless they are licensed and bonded by the state of Washington. I did not know that until receiving an angry letter from the insurance company lawyer. Tail between my legs, I withdrew the claim for $250. In the meantime, Steve told me that Grant finally got the fuel tanks cleaned out, "so he could take his wealthy friends out to have cocktails and watch the 2004 Seafair races on Lake Washington." I later received a legal notice from a different maritime lawyer, asserting a lien against the yacht because the workers cleaning the fuel tanks hadn't been paid.

Steve's doctor, finally paid for by Grant's insurance company, told him he wasn't fit for construction work anymore and that he should find a new career. I jousted with the insurance lawyer for over a year, until just before trial. I knew I had some problems with my case, not the least of which was the delay in Steve going to a doctor. Given all the variables, I thought that $85,000 would be a fair settlement. The insurance lawyer agreed with me and said that he would recommend an $85,000 settlement to Grant and the insurance underwriters if I would do the same to Steve. Grant and the insurance people told their lawyer that they would pay $85,000--and not a dime more!--to settle the case. Steve told me that he would accept $85,000, but only if it came with an apology from Grant for holding up his medical treatment and an acknowledgment that Steve helped save Grant's boat. "My client will never apologize to yours!" The insurance lawyer sounded outraged that I would even suggest such a thing. "I recommended to my client that he settle for the 85 grand, like we agreed, but he says he doesn't care about the money and that an apology is more important. He's adamant. If Grant doesn't apologize, it looks like we're going to trial." The insurance lawyer huffed and puffed about what would happen to Steve at trial, said I was being totally unreasonable by allowing my client to have such ridiculous expectations, and then hung up. There was no jury demand so the judge would decide the case. A few days before the scheduled start of trial, Judge Zilly called the lawyers in for a pre-trial conference in the new Federal Courthouse at 7th & Stewart in Seattle. Sitting before a federal judge--appointed for life--is a pretty intimidating experience for most lawyers. Judge Zilly didn't exactly "read us the Riot Act" about settling the case, but he made it clear that at trial neither side would do as well as they expected. His less-than-cryptic message was: "Go to trial at your peril." As we walked out of the judge's chambers, the insurance lawyer turned to me. "We'll pay $90,000 to settle this case--no apology." I was surprised that the insurance company was offering $5,000 more than its "top dollar" to settle the case. "I'll try to make it happen," I promised as we left the courthouse. I was ready not just to twist Steve's arm but to break it if he didn't accept $90,000 to settle the case without an apology. The newspapers at the time were full of stories about a Seattle vice cop who got busted for corruption. After his lawyer got the case dismissed and the Sheriff Department guaranteed him a pension, the cop told a reporter: "Money is the best way to say you're sorry." I reminded Steve of that sentiment and of what Judge Zilly had said about going to trial. He accepted the settlement offer. Steve sat in my office a few days later, signing papers to end the lawsuit for $90,000. "Grant could have settled this case for $85,000 if he'd written me a short note apologizing for what happened. Does being rich mean you don't have to say you're sorry?" I didn't answer him. The photographs in this article are courtesy of "Steve" and "Tim" (psuedonyms). John Merriam is a former merchant seaman, now a sole practitioner at Fishermen's Terminal in Seattle representing all types of seamen on wage and injury claims. |

|

The yacht met 20-foot seas 300 miles off the coast.

Then the engine stopped working.

Then the emergency battery went out.

The yacht met 20-foot seas 300 miles off the coast.

Then the engine stopped working.

Then the emergency battery went out.

The extra fuel bladders on the afterdeck were intended

to power the yacht all the way to Hawaii.

The extra fuel bladders on the afterdeck were intended

to power the yacht all the way to Hawaii.

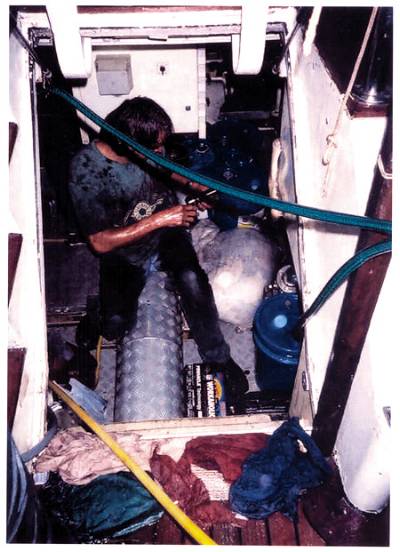

Saved by a garden hose.

The hose served as an emergency fuel line.

The regular fuel line had clogged because of a fuel-tank fungus.

Saved by a garden hose.

The hose served as an emergency fuel line.

The regular fuel line had clogged because of a fuel-tank fungus.